“Stand up straight, sit tall and stop slouching.” How often have we heard this from our parents and teachers? Turns out, they’re right.

Posture influences psychology, comfort, pain, and performance. Good posture results in minimal stress on your joints and supporting tissues while poor posture results in local tissue stress, pain and can eventually cause injury.

WHAT IS GOOD POSTURE?

The definition of good posture needs context for relevance. Consider age, injury history, and current fitness level. Do you have physical stress resulting from an overactive or a sedentary lifestyle? Do you have sufficient rest to mitigate cumulative stress developed from a particular posture?

Experiencing pain while sitting slouched at the computer for half an hour is an example of poor posture. Yet a cyclist flexed over their bike frame to reduce windage is a non-negotiable posture to win. Context is everything.

Standing with the chin protruding and rounded shoulders causes a chronic contraction in the low back extensor muscles. Discomfort, and eventually pain, will result. If you see your family doctor complaining of muscular backache you will most likely get a muscle relaxant and possibly a drug cocktail including an analgesic. But if you saw a postural expert, you’d be coached on how to align the ears over the shoulders, the shoulders over the hips, the hips over the knees and shown how this eliminates the low back muscle activation and pain. But the standing slouch was also a habit. Conscious effort is needed to form a new default habit to avoid the pain mechanism. This is an example of what I call “spine hygiene.” Visit backfitpro.com for many examples of reducing stress and pain.

TO LOAD, OR NOT TO LOAD

Loading a joint at the end of its range often constitutes poor posture. But here not only does joint position matter, but the load matters too. But, what is load? Load increases with escalations in applied magnitude, the number of repetitions, the duration of the load application, but decreases with rest.The greater the load, the more important posture becomes.

Consider an office worker, slouching in their office chair. This may be a good way to relax for a few minutes as long as a disc bulge is not present. But if this posture is maintained for a period of time, eventually they’ll report low back discomfort. Time spent in this posture is the variable that leads to their discomfort and pain.

We’ve all seen someone in the gym performing a deadlift with their spine in a fully flexed position and excessive load on the bar. This singular exercise performed with joints loaded at the end of range of movement is one of the most common causes of why back-pained people are referred to me.

How you respond to load is a variable that is influenced by training. All biological systems have a tipping point. Exposure to the load below the tolerance level of the individual encourages healthy adaptation as long as adequate rest is given to allow the adaptation to occur. But exposure to loads exceeding the tipping point creates microtrauma that will eventually result in injury.

Biological systems are also subject to tradeoffs. In the case of the back and spine, the greater the range of motion, the smaller the amount of load is required to create pain and injury. Good posture—avoiding end-range posture—increases the capacity to safely withstand load; it enhances your training capacity.

Most of the time an instant transformation can be achieved with a sitting and standing posture familiar to anyone who’s ever taken an acting class: the power position. Stand like you own the world, now modify that position to eliminate muscle activation. Biomechanically, body segments are aligned and stacked to reduce muscle tension. Relax with the ears over the shoulders, the shoulders over the hips, hips over the knees, the knees over the middle of the foot. We call it the standing hover. More often than not, this posture will decrease pain.

DOES POSTURE AFFECT PERFORMANCE?

The well-performing athletic body has strategically-tuned joint mobility and stability throughout the musculoskeletal linkage. Core stability enables full power transfer through the hips and shoulders for greater limb speed and application of strength. This is known as the principle of Proximal stiffness enables distal athleticism. This effect can only be documented with case studies since the modification to enhance performance is different for everyone. Over the years we have catalogued extensive case studies in a wide variety of athletes. Thus posture combined with specific muscle activation patterns influence pain-free capacity and athleticism.

But what about awkward postures? Should they be trained, or not? Consider a road cyclist with the spine fully flexed over the bike frame. Assume the athlete would benefit with leg strength and power training and the training exercise of choice might be a back squat with a bar on the shoulders. I choose this specific example because we have dealt with it several times over the years with very high-performance cyclists. Having the athlete adopt their cycling position with load on their back in the gym creates a very poor risk/reward ratio. Specifically, adding load to a fully-flexed spine increases the risk of spinal disc bulges. Thus we enhance the risk/reward ratio by adopting a belt-squat device with the load applied around their waist. This de-loads their spine as they adopt the cycling low-windage position. In this example of cycling, the athlete gets sufficient exposure to spine flexion due to their sport. Adding more exposure to flexion in their training rarely produces a better result. Instead avoiding the vulnerable posture allows a greater training capacity and ultimately higher performance.

HOW TO DO THE STANDING HOVER:

• Feet are shoulder width apart. Try and stack the ears over the shoulders, shoulders over the hips, hips over relaxed knees.

• Feel the low back muscles – they should be relaxed. If you become a peacock lifting the chest it will activate these muscles as will chest slouching.

• Push your toes down into the floor and become a forward-leaning tower through the ankles; shift your weight back to your heels, leaning the tower backwards; now come back, finding the middle ground, and have a look at yourself in the mirror; smile.

In conclusion, a discussion of posture needs context, but within that context good posture increases the capacity to train, reduces pain from overload, and tells the world that you are confident, have a positive outlook and are instantly more attractive.

You may also like: Dr. Stuart McGill’s Secrets to a Healthy Spine

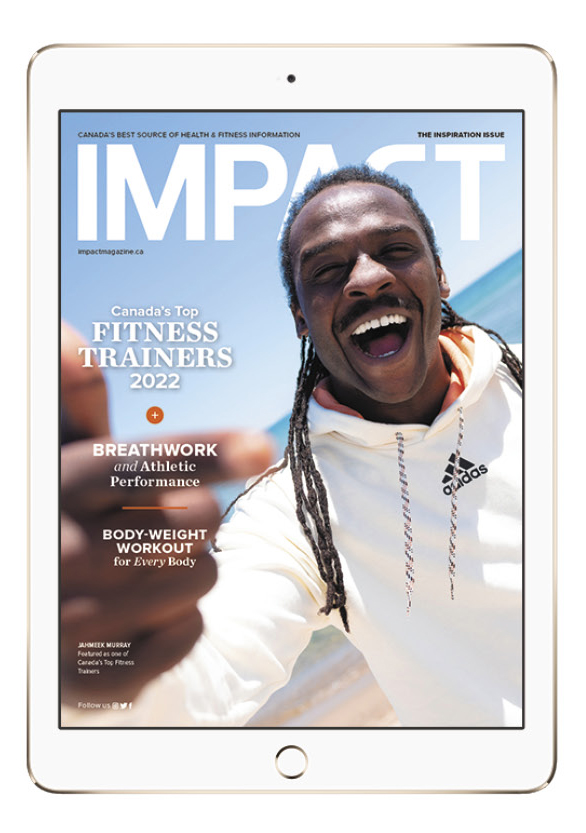

Read This Story in Our 2022 Inspiration Digital Edition

Read about Canada’s Top Fitness Trainers 2022. Need new ideas for your next workout. Test your fitness levels and see how you measure up. World-renowned breath expert, Richie Bostock shows us how to breathe correctly, 7 yoga poses for a better sleep, recipes and much more!