There’s a debate that’s been raging about vegetables for (almost) as long as humans have been eating plant foods: Which is the better, more healthful way to eat them—raw or cooked?

Here’s the good news: It turns out, the answer is both.

Raw foods bring the crunch, and incredible flavour—think of crisp lettuce leaves, brilliant berries, and so on, with no nutrient loss from the heat of cooking. But in some foods, such as carrots, some nutrients are not as bioavailable in the raw state.

Cooking modifies the physical and chemical properties of foods. It causes degradation or leaching of certain nutrients and phytochemicals, but also softens cell walls and other food matrix components, facilitating the extraction and absorption of others.

Every day, we should eat a combination of raw and cooked vegetables. Let’s examine some important points about how our bodies absorb nutrients from food.

Some nutrients can’t stand the heat (or light, or oxygen)

Water-soluble vitamins. Vitamin C appears to be the nutrient most vulnerable to cooking temperatures. About 30 percent of vitamin C in leafy greens is destroyed by cooking. Other nutrients degraded by heat are folate, other B vitamins, and phenol antioxidants. In contrast, minerals and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) are more stable during cooking.

Myrosinase. Cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli, kale, bok choy, and cabbage contain valuable nutrients called glucosinolates. These are converted to cancer-fighting isothiocyanates (ITCs) when the plant cells are broken up by chopping or chewing. Unfortunately, heat deactivates the enzyme (myrosinase) that drives this conversion—but there’s an easy way to get ITCs from cooked cruciferous vegetables: chop or blend the veggies before cooking them.

Add some extra chopped raw cruciferous to the cooked. Chopping (preferably blending) the raw cruciferous vegetables conserves the most ITCs. Once the vegetables are chopped, steaming—compared to stir-frying, boiling and microwaving—resulted in the smallest glucosinolate losses in broccoli. And since the myrosinase is deactivated by heat, you can produce more isothiocyanates from the remaining glucosinolates after cooking by adding some raw cruciferous (such as shredded cabbage or arugula) to the cooked greens.

| Degraded during cooking: | Heat stable: |

| Vitamin C | Minerals |

| B vitamins | Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) |

| Phenol antioxidants | antioxidants Carotenoids |

| Myrosinase | Isothiocyanates (ITCs) – once formed |

The drop in vitamin C and polyphenols with cooking could also limit nitric oxide production from green vegetables. When we chew nitrate-rich vegetables, such as dark leafy greens and beets, oral bacteria convert nitrate to nitrite then nitric oxide, which helps oxygenate tissues better and keep blood pressure down. Vitamin C and polyphenols enhance the conversion of nitrite to nitric oxide. Nitrate is water-soluble, so there may be some reduction in nitrate with steaming or boiling, since the water is discarded, but not with water-sautéing or cooking in soups. Bottom line, eat greens raw and chew well to enhance nitric oxide and make soups your main source of cooked vegetables, which minimizes the nutrient loss from cooking.

Try this: Eat a large green salad, containing a variety of raw vegetables (including cruciferous), with a nut- and seed-based dressing at least once a day. Add some raw cruciferous vegetables (such as shredded cabbage or arugula) to your cooked vegetable meals to increase the production of ITCs and nitric oxide.

Carotenoids become more accessible when vegetables are cooked

Raw carrots have natural sweetness and deliver a satisfying crunch, and fresh tomatoes are tasty in salads, but to get maximum nutritional benefit, bring on the heat too. Carotenoids, such as alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and lycopene are not only heat stable, but actually more absorbable once foods are cooked. Carotenoids are inside the plant cells, embedded in the matrix of the food, and some of the cellular structure must be mechanically disrupted (such as by blending or heating) to make the carotenoids extractable by the digestive system. Vitamin E fractions from plant foods have also been reported to be more bio-accessible after heating. A study on raw foodists found that lycopene status was low without eating any cooked foods. Of course, carrots, tomatoes, and other carotenoid-rich foods contain more nutrients than only carotenoids, so a combination of raw and cooked is ideal.

Adding healthy fats aids carotenoid absorption from raw vegetables

Higher fat intake in the study on raw foodists was associated with better plasma carotenoid status—adding fat is an effective way to improve carotenoid absorption from raw vegetables. One study measured alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and lycopene in the blood after subjects ate salads topped with fat-free dressing, or dressings containing either six or 28 grams of fat. Carotenoid absorption was negligible from the salad with fat-free dressing, and high from the fat-containing dressings. So not merely to enhance carotenoid absorption, but other phytonutrients as well. Though I do not recommend adding oils to salads, it is important to use some nuts and seeds with the vegetable-based meals either eaten separately or as a key ingredient in the salad dressing or sauce. It’s not only carotenoids, using nuts or seeds enhances absorption of other phytochemicals too.

What about frozen vegetables and fruit?

Frozen foods leave some people cold; they associate them with lacklustre taste and low quality. But there’s good news. Yes, the blanching step of the freezing process means frozen produce has lower levels of vitamin C, thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin than fresh. But because frozen vegetables are picked fresh and frozen soon after, a large proportion of the nutrients are preserved.

Compare this with fresh produce, which loses some nutrients during storage, and produce that has been shipped a long distance will likely have less nutritional value than the same produce bought locally. And once the food is frozen, nutrient losses due to storage slow down substantially. For frozen fruits, there is minimal loss of polyphenol antioxidants (such as flavonoids) because fruits are not blanched before they are frozen.

Soups retain nutrients

Soups are satisfying. They’re also a great way to cook fresh and frozen vegetables and retain more nutrients. While some nutrients are not destroyed by heat, they can still be lost in the cooking water if you are boiling or steaming your vegetables. That’s why making a big pot of soup is an excellent way to cook your vegetables—just make sure they’re not overcooked.

The bottom line

A good general guideline to maximize nutrient quantity and variety is to eat a large variety of raw and gently cooked vegetables—large daily salads plus vegetable-bean soups or stews, or vegetables cooked in a wok with water, steamed for only a few minutes, or baked at a low temperature.

Suggested healthy cooking methods for vegetables

- Steam greens in a wok, alternating covering and stirring.

- Steam greens in a steamer for 10 minutes or less.

- Half artichokes up the middle and steam for 18 – 20 minutes.

- Cook carrots and parsnips in soups and stews.

- Bake winter squash at a low oven temperature (325 F)

for one hour. - Wok or steam mushrooms, or add to soups and stews.

- Puree raw cruciferous greens, shallots and onions before adding them to soups and stews.

You May Also Like Eat Plants For better Gut health

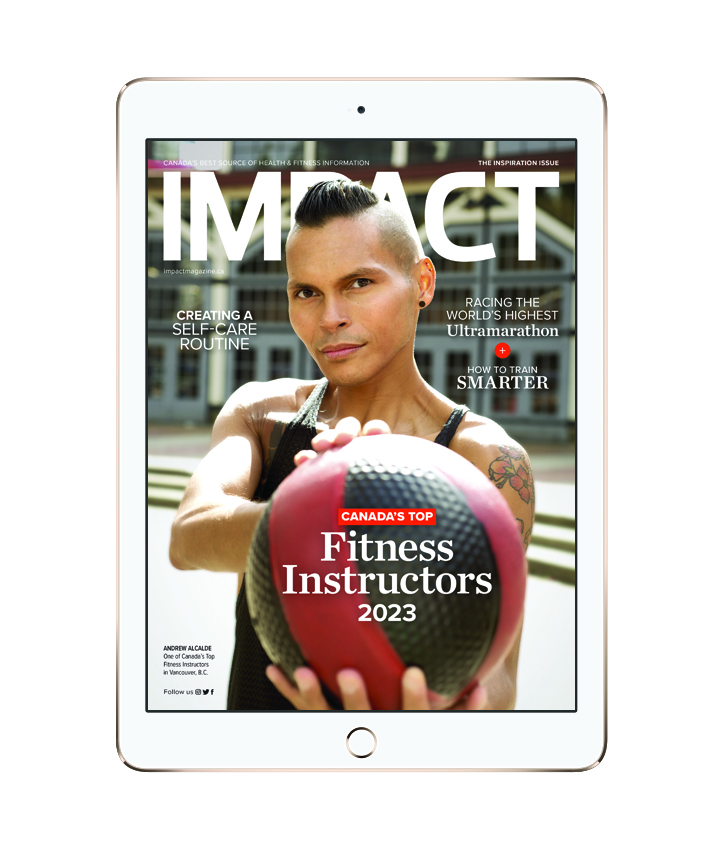

Read This Story in Our 2023 Inspiration Issue

Read about our 2023 Canada’s Top Fitness Instructors – our top 30 from across Canada! How to Train Smarter in 2023, Yoga Nidra for What Ails You, Racing the World’s Highest Ultramarathon, our favourite plant-based recipes and more!