History tells us that our bodies are best understood as machines. Classical biomechanics, brilliant as it is, was developed by studying inanimate, uniform objects: pulleys, bridges, levers. But living bodies don’t behave like dead matter.

As Graham Scarr writes in Biotensegrity: The Structural Basis of Life, “Part of the problem with classical mechanics is that these laws… were described through experiments on inanimate objects with relatively simple and uniform internal structures. Living tissues, on the other hand, are multiscale composites where each anatomical part is a complex module made from smaller modules nested within its complicated, heterarchical organization… and their physiological interactions conform more to the relatively new physics of soft matter than standard engineering.”

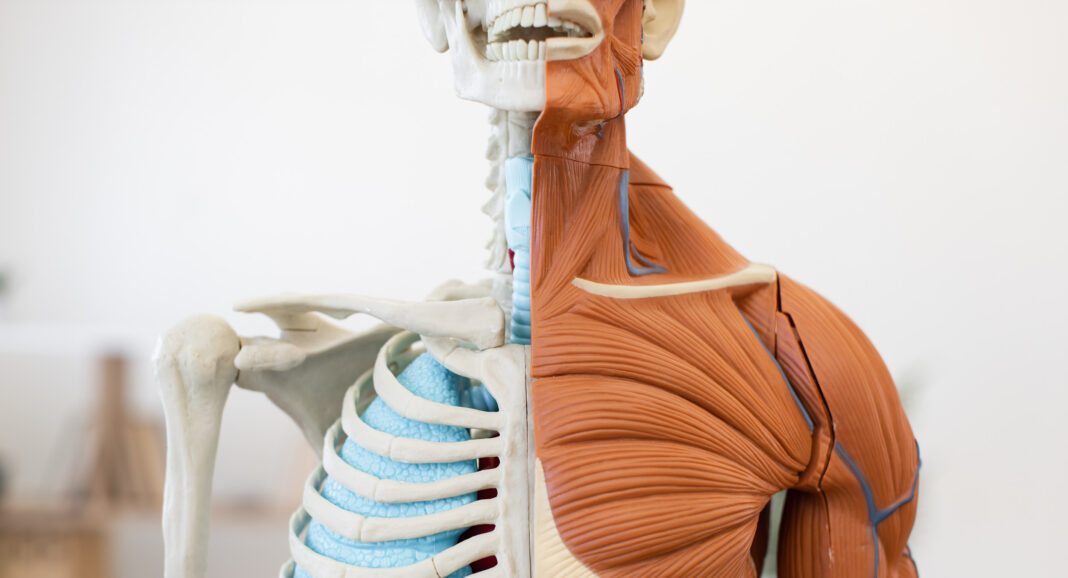

Bones bend. Fascia responds. Tissues under high strain stay supple. Even the most ‘rigid’ parts of the body—bones, tendons—store and return energy like a spring. Structures that would collapse under classical assumptions remain fluid, stable, and alive.

The Cracks in Classical Biomechanics

The mechanical view of the human body found fertile ground during the Industrial Revolution. Giovanni Alfonso Borelli often called the “father of biomechanics,” played a pivotal role in this. His seminal work, De Motu Animalium (“On the Movement of Animals”), laid the groundwork for viewing bones as levers, joints as hinges, muscles as motors. It made sense, especially in a world reshaped by industry. Bodies were measured, mapped, and modeled like machines. Movement was simplified into vectors and torque. Rehab focused on correcting angles and restoring symmetry. Coaching drills emphasized alignment and force production.

But living tissue doesn’t follow engineering rules. Muscles don’t contract in isolation. Fascia doesn’t behave like rope. And forces aren’t neatly transferred along a single axis—they ripple, radiate, and reorganize across the system. Most importantly, real-world human movement is messy, variable, adaptive. It’s not rigid—it’s responsive.

This gap between the predictable world of physics and the emergent nature of living systems is where biomechanics starts to fall apart. Classical mechanics isn’t inherently wrong—it’s just profoundly incomplete for understanding life.

Euclid and Geometry

The problem isn’t just with the mechanics—it’s with the geometry.

Euclidean geometry, first codified by the Greek mathematician Euclid around 300 BCE, offered a logical and consistent way to understand space. His system of points, lines, and angles was so intuitively “correct” that it shaped the way humans conceptualized reality for over two thousand years. Classical mechanics grew within this spatial system—flat, rigid, predictable—and it was only natural that early biomechanics would adopt it as well.

The use of Euclidean logic in biomechanics may help draw diagrams or model force vectors, but it cannot explain how life holds itself together. It cannot model the self-organizing, shape-shifting, heterarchical nature of living movement. For that, we need a different geometry. One that curves. One that responds. One that lives.

Biotensegrity: A New Structural Language

This brings us to biotensegrity, a revolutionary model for understanding biological architecture. The term “tensegrity” was coined by R. Buckminster Fuller, an architect and inventor, to describe structures that maintain their integrity through a continuous tensional network, rather than continuous compression. Think of a tensegrity sculpture: rigid struts (compression) float within a web of continuous cables (tension), holding the shape without touching each other.

Dr. Stephen Levin, an orthopedic surgeon, was instrumental in applying Fuller’s tensegrity principles to biological systems, recognizing that this non-intuitive geometry perfectly describes the human body.

In biotensegrity, bones are the discontinuous compressive elements, ‘floating’ within a continuous, pre-stressed tensional network formed by fascia, muscles, ligaments, and even fluid dynamics. Force is not transmitted through stacked levers but distributed dynamically throughout the entire tensional system. This means that a force applied anywhere in the body is immediately and widely disseminated, allowing for remarkable resilience, adaptability, and energy storage, much like a spring. The body doesn’t stack in segments; it floats in tension.

Heterarchy: Coordination Without Command

A key concept intertwined with biotensegrity is heterarchy. Traditional biological and mechanical models often assume a hierarchy: a top-down control system where the brain dictates every movement, or where one system is inherently more important than another.

In a heterarchical system, there is no single “boss.” Instead, all components—from the molecular level within cells, to the cellular, tissue, organ, and musculoskeletal systems—are equally interactive and influential. They co-regulate through complex feedback loops, adapting and influencing each other in a multidirectional, omnidirectional manner. It’s not top-down, nor is it purely bottom-up; it’s a constant, dynamic interplay from the middle to the outside, from the outside to the middle, from the top to the bottom, and from the bottom to the top. This distributed control and mutual influence allow for incredible adaptability and emergent behaviour in human movement.

What This Means for Movement

The shift from a biomechanical to a biotensegrity and heterarchical understanding of the body has profound implications for how we approach movement, training, and rehabilitation:

- Coaching: We no longer focus on rigidly “aligning bones” or instructing isolated muscle contractions. Instead, the emphasis shifts to managing tension relationships throughout the entire system, cueing for adaptability, responsiveness, and global force distribution. Critically, this also involves designing movement as behaviour aimed at solving problems and tasks. Coaches can leverage task-led constraints to guide the development of motor learning and foster real-world capability, recognizing that movement solutions emerge from the body’s dynamic interaction with its environment.

- Rehabilitation: Injuries are less about a single “failure” at a joint or muscle and more about a multifaceted breakdown in the body’s ability to adapt. This can manifest as a disruption within the tensegrity matrix, a lack of sufficient movement solutions (variability) to effectively solve a movement problem, or even be influenced by lifestyle factors such as cognitive distraction, fatigue, or insufficient readiness for a given task. Treatment, therefore, moves beyond localized fixes to addressing patterns of strain and tension across the whole interconnected system, enhancing motor learning and adaptability, and considering the broader context of an individual’s readiness, fostering systemic resilience.

- Performance: Fluidity, efficiency, and resilience in athletic performance are better understood as the result of distributed coordination and continuous tension modulation, rather than brute-force production by isolated levers. Optimal movement is emergent, not simply instructed, and is always contextual to the task at hand.

The shift from the rigid, linear world of classical biomechanics to the fluid, interconnected realm of biotensegrity is not merely an academic exercise. It is a fundamental re-evaluation of how we perceive, touch, train, and heal the body. You’re not a machine in need of calibration. You’re a constellation of living tensions, adapting in real time to the forces of the world.

This article has been edited for length and reprinted with permission from www.movnat.com

You may also like: Using Nature as Your Playground

Read This Story in Our 2025 Fall Fitness Issue

IMPACT Magazine’s Fall Fitness Issue 2025 featuring the The Fitness Guy, Pete Estabrooks, telling all with his shockingly candid new memoir revealing a story you never expected, as well as former pro soccer player Simon Keith and Paralympian Erica Scarff. Find your ultimate guide to cross-training for runners, no jump cardio and superset workouts along with the best trail running shoes in our 2025 Trail Running Shoe Review, and so much more!