Inactivity is a modifiable risk factor for chronic disease and, according to the World Health Organization,the fourth leading risk factor for death worldwide. Exercise has demonstrated benefits for dozens of chronic diseases, yet 80 per cent of Canadians do not meet physical activity guidelines. So, is it time for clinicians to address the benefits of prescribing exercise (ExRx)?

DEFINING EXERCISE THAT IMPROVES HEALTH

Recent Canadian movement guidelines recommend accumulating at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week. Moderate intensity aerobic activity, such as power walking, swimming, and snowshoeing, makes breathing harder than normal: one can talk but not sing. Vigorous activity increases heart rate and makes it difficult to say more than a few words without needing to catch one’s breath. This can be achieved in team sports such as soccer, basketball, and hockey, as well as cycling, running and uphill climbing—stair climbing, hiking and cross-country skiing.

EVIDENCE FROM SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

We researched systematic reviews of clinical trials done in a primary care setting for adults with and without chronic disease. Various interventions were made on the individuals including anything from writing an exercise prescription (ExRx), to advice or prescribing a free pass to a recreation program.

We identified seven reviews with clinical trials ranging from two to 12 months, but two included studies with over 12 months of follow-up. Five reviews included meta-analyses; four of five found a positive effect of an ExRx (or equivalent) on physical activity levels. The remaining two of seven reviews found mixed results.

These systematic reviews found that exercise counselling is modestly effective at increasing physical activity. For example, a review of 15 trials (with 8,745 people) found that health care providers had to counsel 12 people to get one of them to do the recommended amount of active physical activity for one year (a ‘number needed to treat’ of 12).

The same review identified three trials in which exercise referrals (e.g., to a community centre or walking program) were no more effective than recommendations directly from a primary care doctor or nurse. Furthermore, there is no evidence that recommending any specific type of exercise leads to better adherence.

CAN EXERCISE PRESCRIPTIONS CAUSE HARM?

Two key issues to consider are exercise-induced cardiovascular events and musculoskeletal injury from falls. The risk of exercise-triggered cardiovascular events may be highest in sedentary people, but this can be mitigated by appropriate screening or an assessment before initiating an exercise program. People with low cardiovascular or metabolic risk gain little from screening before recommending exercise.

Most trials did not report musculoskeletal injuries and falls due to exercise. A consistent message from research studies is that the very low risks of an exercise program should be weighed against the clinically important disadvantages of remaining sedentary.

SOME EXERCISE IS BETTER THAN NONE

As mentioned earlier to achieve substantial health benefits, including prevention of chronic diseases or premature death, at least 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity is recommended. However, people who do little or no exercise can improve their health by small changes in behaviour, such as substituting light-intensity activity for sitting time.

The United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) measured physical activity from 2003 to 2006 in 4,840 adults aged over 40 (mean age was 57 and 53 per cent women) who wore an accelerometer for seven days. (An accelerometer is used to monitor frequency, intensity and duration of physical activity). During the follow up over 10 years, the investigators found that: “increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity by 10, 20, or 30 minutes per day was associated with a 6.9 per cent, 13 per cent, and 16.9 per cent decrease in the number of deaths per year, respectively.”

PRESCRIBING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PRIMARY CARE

Helping people change their entrenched behaviours is not easy. There are many common barriers to activity include lack of motivation, insufficient time, pain, or loneliness. Behavioural expert BJ Fogg’s simple model focuses on three factors:

- Start simple

- Find a time when physical activity fits

- Remind yourself to do it

To sum up: we know that physical inactivity is a major but modifiable risk factor for chronic disease. Exercise is medicine. Clinicians should routinely recommend and monitor physical activity options with their patients and stress that even small increases in activity can improve health. In primary care, recommending exercise is good but writing an exercise prescription to increase physical activity is better.

WHAT IS AN EXERCISE (ACTIVITY) PRESCRIPTION?

AN EXRX RESEMBLES A DRUG RX, BUT SUBSTITUTES:

- Type of activity: uphill walking, rowing, skating

- Intensity of activity: gentle walking, moderate swimming, vigorous cycling

- Dose: how much per session, e. g. minutes, steps, distance

- Frequency: how often, e. g. daily, twice a day

- Duration, repeats & review: when?

Your typical prescription from your GP could be: “Walk briskly every day for at least 30 minutes to reduce blood pressure and lower blood sugar. Let’s reassess your progress in four weeks.”

Reproduced from Physical Activity is Medicine: Prescribe It, Therapeutics Institute, University of British Columbia, by Dr. Josh Levin.

You may also like: https://impactmagazine.ca/news-and-views/nature-rx/

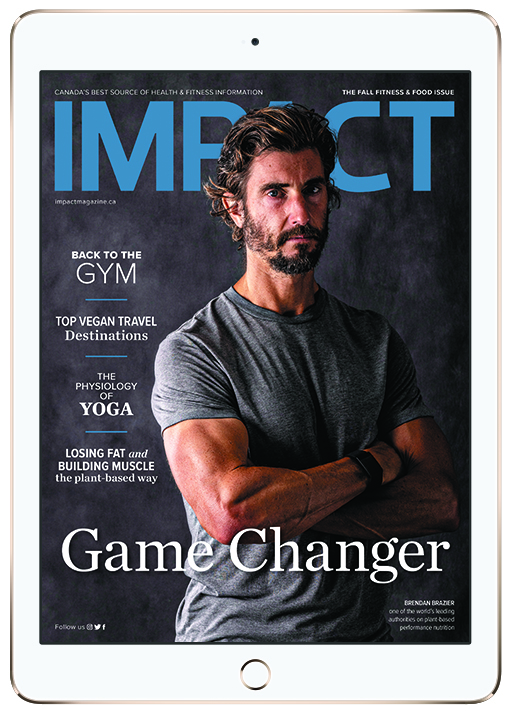

Read This Story in Our 2022 Fall Fitness & Food Digital Edition

Featuring Brendan Brazier, athlete and pioneer in the plant-based sports nutrition industry. Trail Running 101 – plus this year’s Trail Running Shoe Review. Travel around the world to the top vegan-friendly destinations, recipes and much more!