For a non-contact sport, distance running has a pretty high incidence of injury. While there is debate as to the causes of running injuries, training error is one of the most frequently cited issues. Even diligently sticking to a training program may in itself be a training error. While many programs follow a schedule that gradually increases volume and/or intensity, it doesn’t mean that schedule is the one best suited for a particular runner on any given day.

External & Internal Load

Using GPS watches, smart phone apps or other devices gives you an accurate measurement of what is called external load – distance, pace, elevation change and so on; factors that quantify training stress that is outside your body.

A second type of load is called internal load. This includes variables such as hours of sleep, resting heart rate, sleep quality, exercise heart rate, perception of effort, various biochemical markers, heart-rate variability, mood, fatigue and other measurements of internal bodily functions.

Measuring recovery and internal load will let you know when and if you need to change a program or workout. If you’re under-recovered, a particular workout may be too much.

The importance of monitoring external and internal load was highlighted in a report from the International Olympic Committee. A team of sports medicine doctors and sports scientists, led by Dr. Torbjorn Soligard, released a consensus statement in 2017 stating: “Whereas measuring external load is important in understanding the work completed and capabilities and capacities of the athlete, measuring internal load is critical in determining the appropriate stimulus for optimal biological adaptations. As individuals will respond differently to any given stimulus, the load required for optimal adaptation differs from one athlete to another.”

This review included studies involving athletes of all levels from recreational to elite. So, don’t assume that tracking internal load is only for high-level runners.

You don’t need fancy equipment to monitor your recovery and internal training load. A simple daily questionnaire as used by a team of researchers at the University of Technology in Sydney can provide you with reliable information about your internal load. You can use a spreadsheet to track five basic questions rating soreness, stress, fatigue, mood, sleep quality along with the number of hours you sleep.

This method has been validated by another group of sports scientists. Anna Saw and her colleagues from Deakin University in Australia looked at self-reported measures versus objective measures of athlete well-being. Objective measures included attributes such as blood markers, resting heart rate, exercise heart rate, oxygen consumption and so on. Subjective measures refer to items such as mood, perceived stress, etc.

In their paper, Saw and her co-authors wrote: “Subjective measures reflected acute and chronic training loads with superior sensitivity and consistency than objective measures. This review paper provides further support for practitioners to use subjective measures to monitor changes in athlete well-being in response to training. Subjective measures may stand alone, or be incorporated into a mixed-methods approach to athlete monitoring, as is current practice in many sporting settings.”

How To Track Recovery

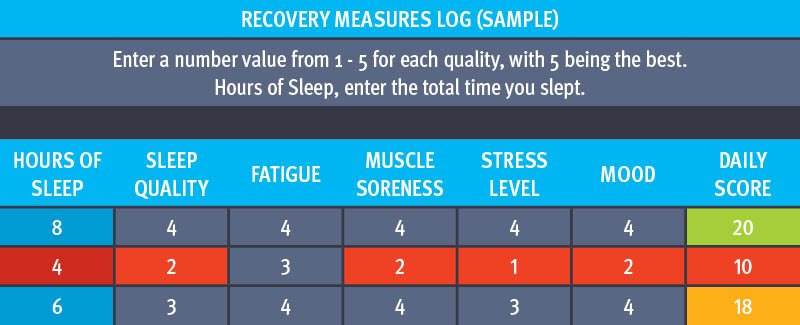

Use this spreadsheet template to track your recovery. Each day, rate these five factors on a scale of 1–5 plus your hours of sleep. The five factors added together will give you a daily score.

A total score of 20 or more is good recovery; between 15 and 19 is moderate and below 14 is poor recovery. On my spreadsheet I’ve coloured the results to make the daily score green for good, yellow for moderate and red for poor.

Here’s a snapshot of a sample spreadsheet with 3 days of tracking these items:

Any day you have a low score and a red flag comes up, be more mindful of how your body is feeling. During your warm-up, pay attention to how your body is responding and progress into a hard workout with caution. If you feel something is off (i.e. a particular muscle tightening up, unable to hit a target pace, etc.) you can back off or cut the workout short.

You should also be looking at trends. Everyone has bad days. And one bad day (i.e. a crappy night’s sleep) may not be reason enough to change a particular workout, such as a long run or hard interval workout. If you see multiple days in a row of inadequate recovery then you’ll want to adjust your training so the external load matches your internal load.

Also look at the individual categories and note if there’s one that scores low frequently. If so, you can focus on taking steps to improving that area. So, if sleep quality is often low, look at strategies and help in getting better sleep.

You can download my recovery tracker at www.corerunning.com or develop your own to monitor your recovery and internal load.