Endurance sport training is awash with new ideas, bandwagons, and phenomena. It’s not uncommon to see athletes and coaches lurching from one new concept to the next. Some examples of these recently have been low volume/high intensity, the Norwegian Method, Zone 2 training and ketones.

None of this is to say that stuff does or doesn’t work, but the attention these methods receive can lead athletes and coaches to change their approach on a whim. So how do you know whether a training method is worth trying or not? The Lindy Effect is the philosophical antidote to this.

What Is the Lindy Effect?

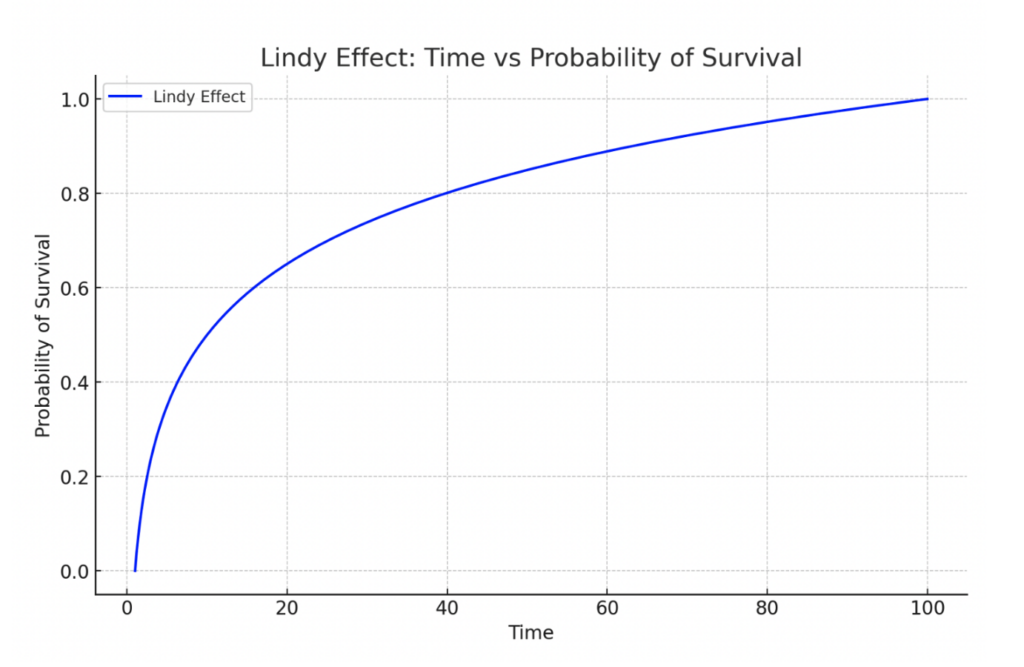

The Lindy Effect is a concept that suggests the life expectancy of non-perishable things, like ideas, technologies, or cultural phenomena, increases with age. The idea boils down to the sentiment that the longer something has been around, the longer it’s likely to continue. It’s a heuristic rather than a hard rule commonly called the “rule of thumb.”

This graph represents the Lindy Effect, showing the probability of survival of an idea, technology, or training method increasing over time. Don’t misunderstand this as dismissing anything new—everything old was once new. Instead, see it as the accumulation of stress over time reducing the fragility of ideas.

Inspired by the Lindy Effect, let’s look at some of the oldest training methods out there.

Mihály Iglói Method

Iglói was a distinguished runner in the 1930s before becoming a coach earning multiple Hungarian championship titles. He competed in the 1500 metres at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, but failed to advance past the heats. In 1950, Iglói became the coach of Honvéd Budapest, the Hungarian army club, where he significantly enhanced the performance of his athletes.

Iglói’s training methodology focused primarily on intervals. The forum on LetsRun.com from 20 years ago has many contributors who were (or at least claim to be) coached by Iglói. They describe a system of short intervals and a lack of planning. The workouts depended on how the athlete felt on a given day, where they were in their training cycle, and their particular event.

“I was coached by Mihály Iglói for about 20 months (1965-66). The majority of my training was either on the grass infield of a 440-yard track or on an extension of that oval that was about 660 yards long. I was interested in marathon training. I did sets of repetitions from 100 yards through to 1000 yards. The pace on any given day could be a mix [of] anything from easy to very hard. As the seasons changed and as the athlete’s shape came up, the intensity and mix changed. All workouts were tailor-made for the individual athlete. It was complex.”

“He would give you one set at a time, and you never knew how much more you were doing that day. He set your workout as you went along based on how you reacted to each part of the workout. He had an uncanny knack of knowing how you felt and how much you could do.”

The pillars of the Iglói Method included:

Interval Training: Frequent, short intervals with varying paces.

Adaptability: Adjusted intensity based on the athlete’s condition and recovery.

Focus on Technique: Encouraged maintaining good form throughout intervals.

While the specific method of running intervals almost exclusively is not common, aspects of his method are practised by world-class coaches today. For example, Dan Lorang (coach of Anne Haug, Jan Frodeno, and Performance Director at World Tour team Bora Red Bull) puts a lot of emphasis on technique during the early phase of his athlete’s training cycle and adaptability is usually preferred over a rigid plan.

Arthur Lydiard Method

Lydiard guided New Zealand through a golden era in world track and field during the 1960s, sending Murray Halberg, Peter Snell, and Barry Magee to the podium at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.

Under Lydiard’s mentorship, Snell secured double gold at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Prominent athletes later coached by him or influenced by his methods included Rod Dixon, John Walker, Dick Quax, and Dick Tayler. Unlike Iglói, Lydiard had no notable achievements in elite running, with a marathon PB of “only” 2 hours and 54 minutes.

Lydiard pioneered periodized training with the philosophy of base training, hills, anaerobic, sharpening, and tapering very similar to the base, build, peak, and taper phases built into many training platforms today.

Lydiard believed in extremely high volume during the base phase, insisting runners did 100 miles per week and 22-mile long runs on hilly terrain.

Base Training (long, slow distance): Emphasised high mileage at low intensities to build aerobic capacity.

Periodization: Structured training into phases (base, hill training, anaerobic, tapering).

Pace Judging: Encouraged athletes to learn to judge their pace accurately.

Many aspects of Lydiard’s system are still practised today, but the primary surviving idea is periodization. Many coaches saw how Lydiard’s athletes would always be in their best shape at the competition.

These are just two of running’s great philosophers, but the fact that their methods are so familiar to us demonstrates the Lindy Effect: the longer an idea has survived, the more likely it is to survive further.

Endurance sport is an industry that’s fragile to fads. Coaches must resist completely changing their philosophies and instead focus on what works. That’s not to say they should resist all new ideas, but only implement these in areas where the risk of departing the tried-and-tested ideas is worth the reward.

This article has been edited for length and reprinted with permission by TrainingPeaks – www.trainingpeaks.com

You may also like: Caffeine and Sports Performance

Read This Story in Our 2024 Fall Fitness Issue

IMPACT Magazine Fall Fitness Issue 2024 featuring Canadian figure skating icon Elladj Baldé, Paralympic shot putter Greg Stewart, Indigenous rights trail running Anita Cardinal. Adventure travel with some amazing winter getaways, strengthen your back and hips, find the art of joyful movement, Inclusivity in the fitness industry and so much more!