I took my seat at the long wooden dining table at the historic Wakefield Mill Inn and couldn’t help but smirk at the irony unfolding. The soft candle glow of the rustic room, coupled with the upscale elegant place settings seemed out of place for the motley crew of runners at the feast — rough, tough, hungry and raring to go. How fitting that we were dining in what was once the engine room supplying power to a flour mill established in 1838. Indeed, the calories inhaled at this meal would be fuelling our engines for the epic journey ahead – 150K of semi-supported trail running through historic Gatineau Park.

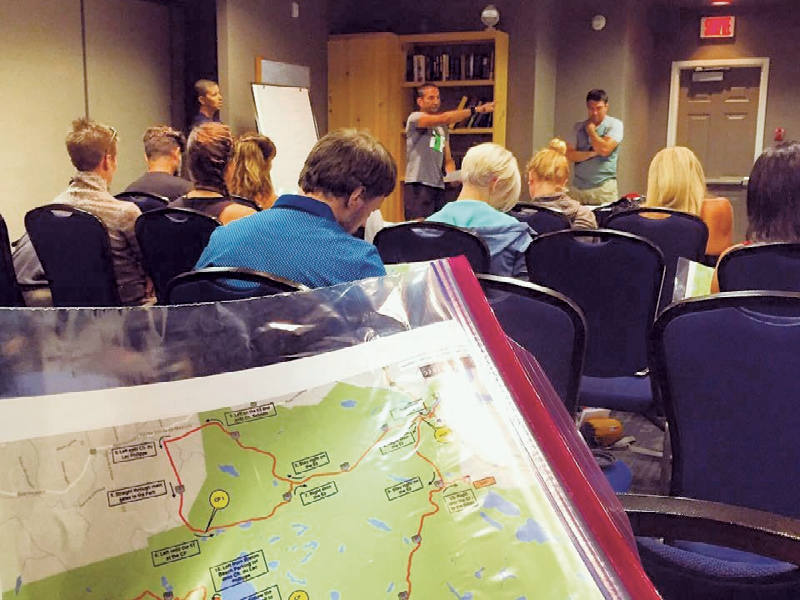

As we broke bread and drank, 20 of us took turns spinning tales of past adventures and pondering the one yet to come. There were the mysterious Italians, sharing their centuries old secrets of cheese. The illusive expat, living in New York, trying to reclaim his stake of the great Canadian north. The jovial Brit (there’s one at every stage race) and of course, the crazy Canucks — wondering where the poutine was. We were attempting to make history on land saturated in it, running the inaugural Bad Beaver Ultra in the footsteps of Canadian forefathers such as prime ministers Lester B. Pearson and William Lyon Mackenzie King. Would their ghosts haunt us along the way? Or would they chuckle at this gangly group trying to become Bad Beaver pioneers in the heart of the land they once governed.

The following morning, we gathered outside the mill at dawn — poised and anxious to run. Andy Roberts, a retired botanist and fellow runner, educated me on the noxious plants in the area. “Stay away from the wild parsnip,” he advised. “Don’t brush up against it, whatever you do.”

“Thanks, Andy,” I muttered. If the heat and humidity didn’t kill me, the parsnip surely would. Or maybe I would fall prey to the illusive coywolf, a coyote-wolf hybrid lurking in the woods. The thought of being bitten and morphing into a trail-running werecoywolf made me howl.

Like many multi-day running events, this one had its fair share of natural threats and thrills. And as the race began a few strides from the MacLaren Cemetery, where Pearson’s grave is marked, I recalled a story about the former prime minister’s entrance into the First World War as a stretcher bearer with the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Perhaps one of us would call upon those services. Perhaps Pearson’s spirit would have a chance to treat the wounded once again?

Over the next three days we would grind through a series of technical trails, forest track, waterfalls, caves and more, all while earning a lesson in Canadian geology, geography and social studies, whether we knew it or not.

Navigating the icy waters of the Lusk caves offered a much needed cool down from the searing August heat for those who braved the dark cavern. The sculpted marble tunnels were the result of the Ice Age, a time thousands of years ago that saw the Wisconsin Glaciation cover most of Canada, freezing as far down as the state of Wisconsin.

Descending the slippery rocks to the mouth of the cave, common sense reasoned against taking another step. As usual, my curiosity screamed a little louder and I pushed deeper into the abyss. As the cavernous ceiling dropped, I submerged in murky water up to my neck. Navigating by headlamp proved to be useless as the steam radiating off my body overpowered any light from my torch.

I pushed deeper into the cave.

Like the Lusk Caves, Luskville Falls was named after Irish pioneer Joseph Lusk and offered its own stiff challenge. The steep ascent up the Eardly Escarpment in debilitating afternoon heat proved to be the knockout blow for more than one competitor. Those who conquered the north summit could pause and admire the Ottawa Valley before stumbling down the mountainside onto a 3K stretch of asphalt surrounding Meech Lake. It was here that “11 men in suits,” as the First Ministers were described, negotiated to amend Canada’s constitution by declaring Quebec a distinct society. And much like the ill-fated accord, as I stumbled down the shoreline, my shoes fell apart.

Later that night, after covering more than 75 kilometres for the day, stumbling between a black bear and her cubs and being slugged by a torrential downpour, race director (and self-appointed triage nurse) Ray Zahab would declare my shoes dead, with my left foot suffering a torn ligament.

“It’s gonna hurt like hell, but you’ll finish,” Zahab says.

The final morning saw us depart Camp Fortune, climbing the local ski hill through evergreen forest before winding down the back side on a professional mountain bike trail. As I fell in cadence with my running buddies Troy and France, time seemed a blur. Before we knew it, we were making the final ascent up the crest of King Mountain.

Named after William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada’s 10th and longest serving prime minister, the heritage site serves as a token to his legacy. The stamina it took us to make it this far was matched only by Mackenzie himself. Imagine what it took to serve as prime minister for nearly 25 years, including the entirety of the Second World War.

With the finish line only kilometres away, my shoes gripped some of the oldest rock formations in the world, striding over the Canadian Shield. It felt surreal to lift off from the very spot where a copper survey bolt marked the original survey of Canada. For us, it marked the end of our journey.

The final steps passed through Mackenzie King’s magnificent estate. The land, once owned by King, was donated for all Canadians to enjoy, including trail runners and werecoywolfs alike.

For the final 10K, my trailmate Troy and I had been reciting a motto passed down from my father: “10 kilometres for the rest of your life, 9 kilometres for the rest of your life,” and so on… until we tumbled across the finish line, raising our arms in victory.

On a balcony with a cold beer in hand, I looked out over the thick canopy of trees and felt the ghosts of Pearson and King grinning down upon us … pondering the folly of these modern Canadians, these Bad Beaver pioneers.