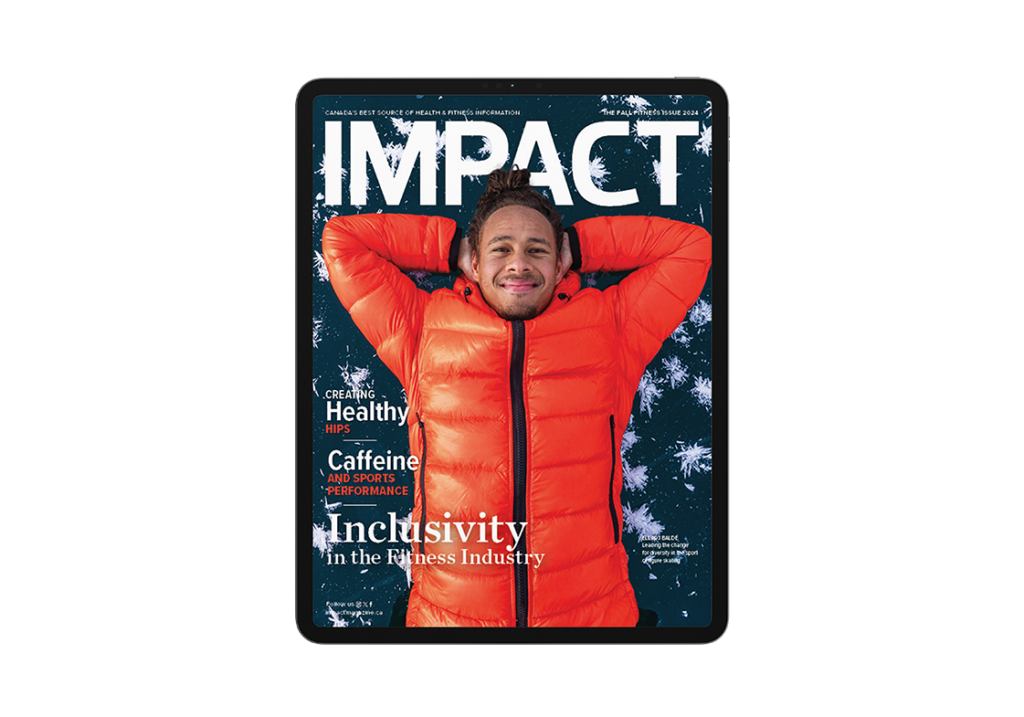

As a young boy climbing the ranks of professional skating, Elladj Baldé dreamed of Olympic glory, but little did he know his legacy in the sport would be something much greater.

Some might say that skating was in Baldé’s blood. His mother had been a skater in Russia in her youth, and so had his older sister, who was eager to one day teach him how to skate. Tragically, she passed away from leukemia at the age of seven, before she ever got the chance.

Born in Moscow to a Russian mother and a Guinean father, Baldé moved to Montreal with his family when he was just two years old, shortly after the loss of his sister. When Baldé turned six, his mom took him to an outdoor rink where he discovered his own love of skating, following in her footsteps and those of his late sister.

“I felt very comfortable very quickly,” he recalls. By the time he was six-and-a-half, he was already competing. He had a Russian coach to push him hard and the weight of the world on his small shoulders. “It was ingrained at a very young age—you skate in order to be the best. It’s not just for recreation. It’s not just for fun.”

As the 34-year-old explained, a lot of Russian people took their families out of poverty through skating, so the pressure to perform was immense from the onset. As a result, he immediately hated competing and would pray for delays on the way to competitions, hoping they would arrive too late to participate.

It all changed when he discovered jumping. He had a unique ability to land jumps that kids his age couldn’t match. When he incorporated these jumps into his performances, he started to win competitions. With each victory, his belief grew: this could be his path. He was destined to be a champion—an Olympic champion.

“That’s what I believed I was going to be and nothing less. A silver medal would have been devastating,” he says. “That’s a lot to carry as a kid who is just starting to skate.”

Through the years, the pressure continued to mount. His love of jumping—and his natural ability to do it well—carried him through the categories of the sport. Although he had medalled in and won competitions, none of that mattered to Baldé. It was to be Olympic champion or nothing.

He can clearly see the mental health implications such a mindset had through his pivotal years, but he also believes he needed that mindset to push himself and get the job done. Eventually, however, that mindset wasn’t enough.

Baldé had his first shot at the Olympics in 2014. It wasn’t just any Olympics though; it was the Winter Olympics in Sochi. It would have been perfect. Baldé would return to the country of his birth for the first time to compete for glory. He would finally reach that pinnacle of skating he had worked so hard to achieve. But he didn’t make the Olympic team.

“My entire self-worth and validation were built around this idea that I was going to be an Olympic champion, and when I started to realize maybe that wasn’t my path, things got pretty dark,” says Baldé.

The turning point in his life came after he competed in the 2015 Canadian Tire National Skating Championships. Not only did he place sixth, losing the competition he was confident he would excel in, but he didn’t even place high enough to make the national team.

At the same time, Baldé’s father was encouraging him to come to Africa to meet his 99-year-old grandfather, who was in ill health. After the loss at nationals, he decided to make the trip—a decision he says transformed his life.

He went to Africa, vowing not to step on the ice again until he found a deeper reason to perform. He skated to please his mom and his coaches. He skated to win. He skated to feel validation, and he skated to become an Olympian. But there was no motivation coming from within. That all changed on his trip.

Being around his family, he recognized their unconditional love and their connection to each other and to nature. Witnessing that deep connection in the mountains of Guinea, far from the world he knew and far from a cellphone signal, Baldé’s perspective changed. He realized there was something so much more important than his own goal of winning. No longer would he skate solely for the results. He would skate to tell his story and let his authentic self be free.

As a biracial skater, Baldé says he was forced to fit into a box during his career. He couldn’t dance to his favourite hip-hop music. He couldn’t wear the clothes he wanted to wear. He recalls he was told to cut his hair short because the judges wouldn’t like “curly, nappy hair.”

“I was giving parts of myself away for the sake of success.”

Now settled in Calgary, Baldé has found an outlet to share himself with the world. With the help of his now wife, Calgary native and professional choreographer Michelle Dawley, he has become a sensation on social media, expressing himself with the moves he wants in the place he feels most free—under the wide-open sky on the majestic frozen lakes in the Rocky Mountains.

“It opened me up in ways I never expected. It started to heal my relationship with skating,” he says.

Baldé faced another pivotal moment in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd. He connected with Black skaters around the world, and they shared their experiences in the sport. What they found was that regardless of where they came from—Australia, France, South Africa, Canada—they all shared similar stories of racial oppression.

It was then that Baldé and several of his skating colleagues founded the Figure Skating Diversity and Inclusion Alliance (FSDIA). The organization was founded to create a safe space for Black athletes and hold the sporting organizations accountable for their promises of inclusivity.

With the dream of bringing about even more change, in 2021 Baldé and Dawley created the Skate Global Foundation, a not-for-profit organization focusing on equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI), mental health and climate change.

“Those are three things Michelle and I are extremely passionate about,” says Baldé, explaining that most of the projects have so far focused on EDI. “That’s where I feel I can have the most impact right now.”

One of the foundation’s first projects was partnering with a construction company in Calgary to refurbish an outdoor rink in an underserved community. The foundation is now working on a project to provide grants to competitive skaters of colour to alleviate the sport’s financial burden. As Baldé explains, it’s easy to get priced out of skating, and it often happens to families of colour. Grant applications closed in August 2024, with recipients to be selected in the coming months.

Baldé and Dawley have big ambitions for the Skate Global Foundation, and they want to expand operations to support more athletes. Baldé admits they have to be patient as they continue to build, as the kind of exposure and support they need won’t come overnight.

“This is important, so we’re going to start small and keep building and building,” he says.

Another passion project of Baldé and Dawley’s is the Art of Performance, their training camp for figure skaters. The camp touches upon the technical side of skating—the jumps, the spins, the skating skills—but the deeper intention is to create a safe space for young skaters to develop themselves as artists and allow them to tell their own stories.

The Art of Performance teaches skaters to embrace discomfort, helping them learn to cope with the pressures of competing in a judged sport. “You’re constantly in your head about what people are thinking. You constantly feel like you’re not good enough,” says Baldé about the toll competing can take on mental health. “We encourage [the skaters] to believe in themselves.”

The camp will be back at Winsport in Calgary in May of 2025 for the second year in a row, thanks to an incredible partnership with the Canadian Sport Institute Alberta (CSIAB), who teach the skaters off-ice essentials like nutrition, proper warm-ups and cool downs, mobility, strength and conditioning, and body positivity.

“The Art of Performance showcases how performance is not just about technical skill but also about emotion, creative storytelling, and expression,” says Kelly Quipp, exercise physiology lead and sport physiologist at CSIAB. “Elladj uses the Art of Performance to share his talent of pushing the boundaries of performance and inspires others to do the same.”

Baldé might not have set out to be a role model for skaters of colour but by shining the spotlight on inclusivity and mental health in the sport, he’s inspiring many and sparking big change in the world of skating.

Photography by Paul Zizka

You may also like: Cover Stories

Read This Story in Our 2024 Fall Fitness Issue

IMPACT Magazine Fall Fitness Issue 2024 featuring Canadian figure skating icon Elladj Baldé, Paralympic shot putter Greg Stewart, Indigenous rights trail running Anita Cardinal. Adventure travel with some amazing winter getaways, strengthen your back and hips, find the art of joyful movement, Inclusivity in the fitness industry and so much more!