Fasted training sessions and intermittent fasting are creating quite the buzz with the promise of weight loss and performance benefits. And seemingly everyone is doing it, so what could be the harm? If you’ve ever jumped out of bed for an early morning workout without eating and didn’t grab a banana or bar, then you’ve done a fasted workout. Some athletes consciously forgo eating since they feel better training on an empty stomach, while others claim pre-fueling isn’t high on their priority list.

Scientific literature defines fasted training as not eating within 10 to 14 hours before a workout. For most athletes, this applies to their morning workout or to someone who eats breakfast then goes all day without eating and then works out.

Some experts say exercising on an empty stomach is the best-kept secret, yet others warn against it. So, let’s sift through the chatter and find what works best for you.

What’s the benefit of running on empty?

The allure of fasted workouts hinges on the promise of burning more fat as fuel, weight loss, a leaner physique, and enhanced performance.

However, because our glycogen stores are limited, fasted training forces the body to utilize fat. Over time, with adaptation, the body will learn how to burn fat, versus glycogen, providing sustainability during longer aerobic runs. Reliance primarily on fat for fuel versus carbohydrate (carbs) delays the immediate risk of bonking and helps reduce reliance on supplemental fuel. All this to say, the theory of burning fat over carbs supports weight loss and a leaner physique.

Collectively, the research is clear; training in a fasted state improves the ability to tap into fat stores sooner and burn a higher percentage of fat during training sessions.

However, beware—the body is smart! In a fasted state, training the body to burn fat will promote intramuscular fat storage, and overtime this plan will backfire.

The red flags

Although fat is the primary fuel source in fasted, aerobic workouts, depending on the workout intensity or duration, the body will select the best fuel sources (fats, carbs, and protein) for energy production. In non-fasted endurance training, protein contributes approximately five per cent of energy. However, in a fasted state, the amount of protein breakdown in muscles is double. Breaking down muscle tissue leads to a decrease in resting metabolic rate, a reduction in strength, poor performance, and ultimately can lead to injury.

Training in a fasted state to delay or avoid bonking may sound like a good idea, but research warns it’s a major physiological stressor for the body. Athletes who train under-fueled experience elevated cortisol levels, deep fatigue, poor recovery, abdominal fat storage, and systemic inflammation. Breaking the fast by eating just enough to bring cortisol levels down will allow the body to access carbs and free fatty acids so you are physically able to hit top-end efforts in training and thus enhance fitness.

Athletes tend to underestimate caloric needs and sacrifice carbs in our carb-phobic world. Training under-fueled can signal restricted eating and may lead to disordered eating or a full-blown eating disorder. Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) or low energy availability is rampant in the athletic population from novice to pros, and any time an athlete restricts food to improve body composition or performance, it signals an alarm.

Finally, research suggests the consequence of negative energy availability among female athletes comes at a higher price than their male counterparts. Not to suggest fasted training is appropriate for male athletes, but females are different due to their hormonal makeup. In the female monthly cycle, there is the follicular and luteal phase, low and high hormone, respectively. In the luteal or high-hormone phase (day 15 to 28), both estrogen (anabolic) and progesterone (catabolic) are elevated. Estrogen promotes fatty acid oxidation and spares glycogen. Therefore, the female athlete is an efficient fat burner since this occurs monthly for 35+ years. Progesterone dampens the body’s ability to store glycogen, so in the high-hormone phase, the body instinctively leans on fat over carbs for fuel. In this phase, fueling needs change depending on the intention of the session.

When is it okay to run in a fasted state?

If you can’t stomach eating before a run, it’s okay to go into the session fasted—some of the time—as long as the effort is easy,

60 minutes or less in duration, and you are adequately hydrated.

However, topping off blood sugar after an all-night fast boosts blood glucose and energy, improves mental clarity and mood, allows the body to better access carbs and free fatty acids, and hinders muscle breakdown during the session.

During high-intensity sessions and those over 75 minutes it’s best to top off blood sugar with approximately 150 calories made

of 20 to 25 grams easy-to-digest carbs, low fat, and fibre, with sodium and some protein.

Examples include applesauce, white bread, banana, non-sweetened instant oatmeal with almond milk watered down to drink, rice or potatoes, sports bar, figs, dates, protein latte, or two to three sports chews.

During the session, fuel with a sports-hydration beverage and possibly supplemental fuel. Fueling during a session provides an opportunity to test drive race-day fueling/hydration and train the body to digest at higher efforts.

On long runs, it would be wise to simulate race day with a “pre-race” breakfast within a one-to-three-hour window before you head out. Why wait until race day to simulate how you fuel for the race?

Prioritize a post-workout snack within 30 minutes after high intensity, long, and strength-based workouts, or if you can’t eat a meal within that time aim for 25 grams of protein with some simple carbs, low in fat and fibre. Examples include whey protein shake, Greek yogurt, protein bar, chocolate oat milk.

The final bite

When in doubt, always go back to the basics. Ask yourself, are you eating enough carbs, protein, and fat to meet energy demands, maintain health, and optimize performance?

Is this an eating regimen you can or should keep for life? And, if it’s not sustainable, then what’s the end goal?

Here’s a concession, if you want to include a “fast” in your dietary regimen, consider fasting from right after an early dinner until the pre-run snack or breakfast the following morning. That will deter mindless night snacking, likely void of nutrients and help shed those unwanted pounds.

This article has been reprinted with permission by Susan Kitchen from www.racesmart.com.

You may also like: Nutrition for Endurance

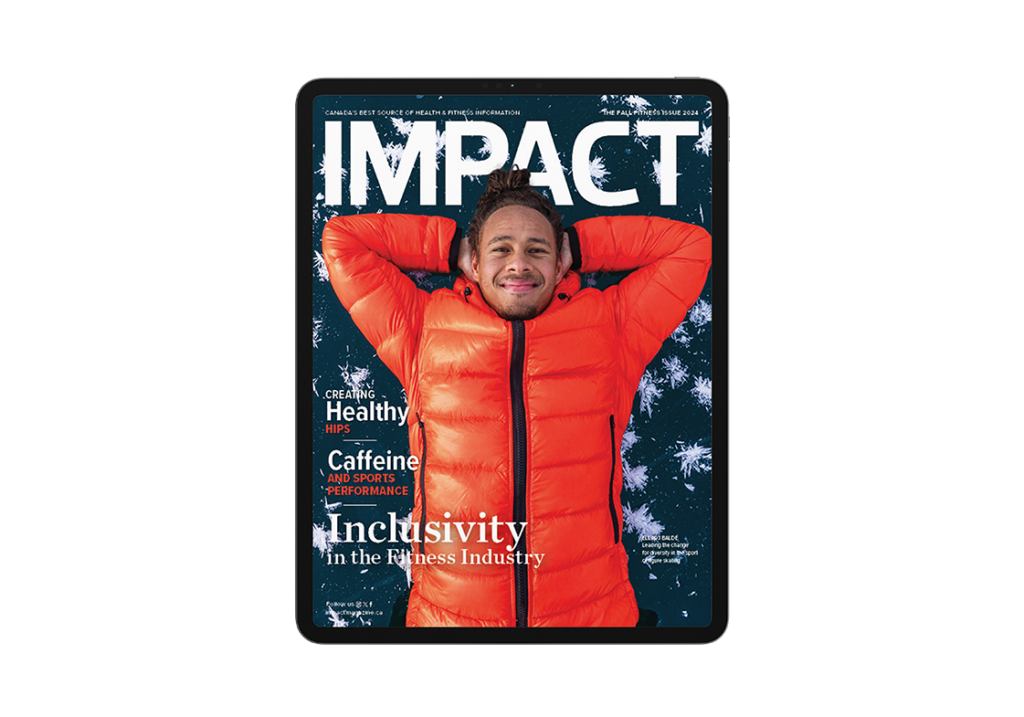

Read This Story in Our 2024 Fall Fitness Issue

IMPACT Magazine Fall Fitness Issue 2024 featuring Canadian figure skating icon Elladj Baldé, Paralympic shot putter Greg Stewart, Indigenous rights trail running Anita Cardinal. Adventure travel with some amazing winter getaways, strengthen your back and hips, find the art of joyful movement, Inclusivity in the fitness industry and so much more!