They call the Tsingy de Bemaraha forest the land where one cannot walk barefoot, a landscape of limestone spires and dry tropical forest in western Madagascar. Bekopaka, in the south, is a tourist hub. The northern portion of the forest remains wholly untamed and unexplored — a wild mystery on the map.

Through millions of years of erosion, the Tsingy has taken on fantastical forms unlike anywhere else. It is home and refuge to unique, endemic fauna and flora; one of the few remaining dry tropical forests of the world. The Tsingy is designated as a national park and nature reserve, ensuring continued refuge for its many endemic species.

I’m here with a team of endurance athletes, but our race is in the name of science, a mission to explore and map the labyrinthine limestone passages of the Tsingy — among the few remaining blank swaths on the global map — to search for archaeological artifacts and dinosaur tracks and conduct lemur surveys. Our finish line is measured by our limited supply of food and water and by the quenching of our thirst for adventure.

Madagascar is an island nation that sits in the Indian Ocean 400K east of mainland Africa. We are here to explore this uncharted territory and our passions, exploration and endurance, provide means to reach and reveal the unexplored.

Our team, a dozen athlete-explorers with the Alberta-based group Adventure Science, arrived in the capital, Antananarivo at the start of October and flew to a remote outpost in the western lowlands. Stepping out of a small fixed-wing plane onto the unkempt landing strip of sand and scrub, we shouldered our packs and dragged our duffels around colonies of termite mounds to waiting vehicles. Heads bobbled through the open windows and off the roof as we navigated drying creeks, muddy embankments and parched savanna on our way to base camp on the northern edge of the Tsingy. Our tents huddled against a murky river under dry palms and lianas.

The burning excitement we arrived with was quickly reduced to a smoldering mess of embers. Keith Szlater, our basecamp manager, is a man with back-up plans for his back-up plans, yet his nerves were already frayed. He had arrived two days earlier with Simon Donato, Jim Mandelli and Travis Steffens. Those three left Keith at basecamp and ventured into the Tsingy on a reconnaissance mission. Despite being endurance specialists, the fortress of stone and tangled vegetation had taken them hostage. They were out of food, being baked in the equatorial oven, and drinking from the single scummy pothole they could find.

Back at basecamp, we scrambled to come up with a way to get the guys out. I packed a bag with rescue gear. Tim Puetz, our Army Ranger turned physiologist, and Tyler LeBlanc, our medic, readied too. As we headed out, word came that the Malagasy military would retrieve the boys by helicopter. We waited for the rescue to arrive. Keith recalls, “The toughest part of the rescue was knowing the clock was ticking and if the helicopter extraction failed then there was a high possibility that people were going to die.” The trio straggled back into camp the next afternoon after two days and nights stranded, thirsty but unscathed.

The next morning we marched right back down the same path that swallowed the boys. This time, we were armed with the hard-earned, calorie-deficient, severely dehydrated experience from the “reconnaissance.” We brought snacks and left a trail of ribbons to lead us out of the maze.

I am adept at moving quickly over technical, nasty terrain. I enjoy the ease with which my body moves over rooty west coast trails, steep scree in the Rockies and mud and moss in the Laurentians. This skill provides little traction in this unknown world. Travel through the labyrinth is incomprehensibly languid. The raw physical battle of forward progress is humbling. Our daily trek from basecamp to the Hub — an opening into the labyrinth fortress — was less than 1,500 metres. Clawing through vines and snagging brush, squeezing through cracks, and jumping across creeks became an hour-long affair.

The limestone is striated — stone-corduroy towers — with ridges running from ground to sky. The fields of stone are cracked and fissured leaving hallways wide enough to walk through. Some require shimmying with backpack in hand while others are barely wide enough to trace the light through. Calling the rock sharp sells it short. I slashed my shoes into pieces on day one by catching my toe on an innocuous block, leaving me with reverse flip-flops for the rest of the adventure. My clothing, backpack, knees and hands met the same flayed fate.

Navigating the passages is gnarly work. One crawl was named Shawshank after the memorable tunnel Tim Robbins escaped through in Shawshank Redemption. Others are so cozy that stomach and back are simultaneously shredded. Each day we were coated in dirt and the barbs of vines and leaves that begged us to stay. Our shirts underwent a steady transformation from white to gross.

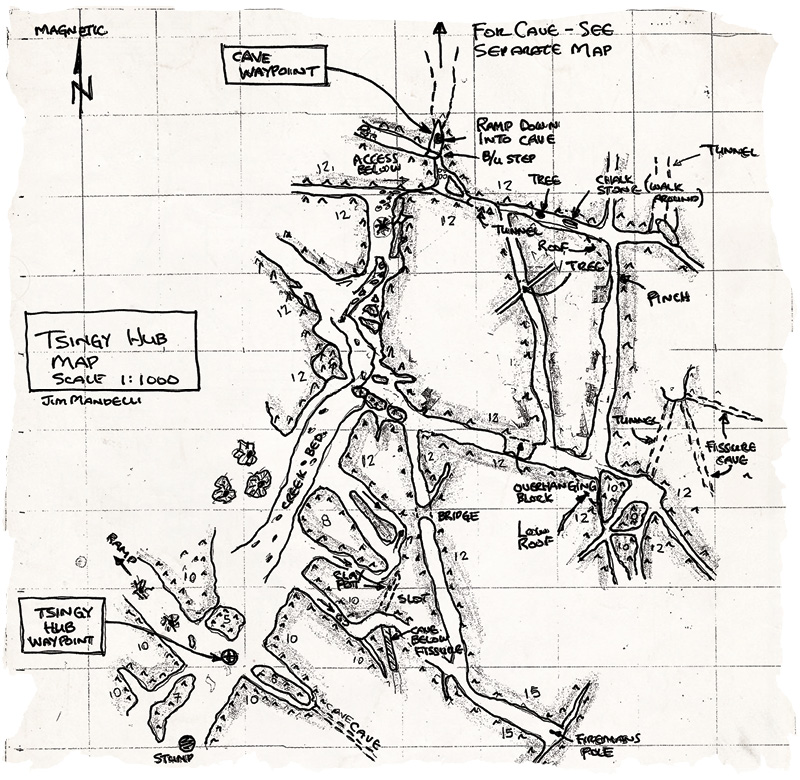

We wandered through the stone maze searching for archaeological artifacts, biological oddities and, occasionally, each other. Most of the team traipsed around poking about in small caves, climbing monstrous vines and identifying passing lemurs and lizards. Jim Mandelli and I were tasked with mapping the labyrinth by hand. We measured, sketched and set bearings from morning to evening.

“Knowing one of our roles was to map the Tsingy left me speechless,” says Mandelli. “We just walked around to get a feel for the Tsingy and I distinctly remember thinking, ‘Damn! This will be a challenge.’ But as with any large task, just pick a starting point and be methodical. The only real way to map the labyrinth was to patiently map one corridor at a time and do it properly — to scale and using a grid and compass. Once we got started it was not so bad.”

Jim and I mapped about 1K of the Tsingy by the end of our exploration.

Tyler LeBlanc discovered a ceramic pot in a small cave. The squat vessel, adorned with parallel bands, had likely endured the elements since the 1600s. It was the only evidence of human experience in the stone maze. Tim found a gargantuan 1,600-metre cave with its many channels extending from a central ballroom. Our Malagasy guides named it Anjohibetsara, “big, beautiful cave.”

We spent three days exploring Anjohibetsara. Jim and I mapped again, this time by the narrow shaft of light from our headlamps. I crouched and crawled through the dank, pitch-blackness, dodging bats and a perturbed cave owl while trying to draw my way out. Each day, a hefty black wasp with gangly orange legs the length of my fingers and wings reverberating like a helicopter slowly passed us as it moseyed through the tunnel. We marvelled over marbled flowstones and contorted stalactites. Our entire team waded through a chest-deep water channel alongside cave shrimp.

After a sample of dark days and maze wanderings, four of us turned to the hunt for dinosaurs. We hiked across an ancient coastline searching for tracks. We missed the tall shadows of the stone walls. In the sun, temperatures reached 50C. Without access to basecamp, we carried our equipment, food and water — 13kg of water. Over nearly 35K, we watched for prints hidden in the sand. We swept dried creeks clear with a branch, leaving dust clouds behind. Somehow, despite needle-in-a-haystack odds, Jim unearthed two separate tracks from a therapodic Velociraptoresque species — a score of six steps over three days.

We stepped out of the Tsingy after two weeks of exploring and adventuring. The team was a grubby bunch upon boarding the shimmering white charter back to ‘Tana. Though exhausted, I left appreciating the unique and extreme challenges of the Tsingy, fulfilled with an understanding that through a practice of endurance we had unearthed a bit of the mystery of the unexplored — a perfect well of inspiration for when I’m digging deep during my next long race in the wild.

Photo: Adventure Science

Explore Madagascar

- Flights to Antananarivo travel through Paris.

- Total travel time from Canada is approximately 36 hours. Round-trip flights start at $1,200.

- Madagascar is home to approximately 23 million people.

- Malagasy is the native language though many people also speak French. Madagascar was a French colony until 1960.

- Malagasy diet revolves around rice. It is prepared for all meals and most dishes in Malagasy cuisine.

- Forestry and agriculture are prime industries. Madagascar is the world’s primary supplier of vanilla, cloves and ylang-ylang, as well as many precious stones including sapphires.

- Moraingy, a martial art, and zebu (native cattle) wrestling are traditional sports. Rugby and soccer are also popular.

- The island’s climate is split between a hotter wet season (November-April) and cooler dry season (May-October), when most foreigners visit.